The title of a new study asks “Does WISC-IV underestimate the intelligence of autistic children?” The authors’ answer is that it probably does. I believe that the reasoning behind this conclusion is faulty.

This study gives the unwarranted impression that it is a disservice to children with autism to use the WISC-IV. Let me be clear—I want to be helpful to children with autism. I certainly do not wish to do anything that hurts anyone. A naive reading of this article leads us to believe that there is an easy way to avoid causing harm (i.e., use the Raven’s Progressive Matrices test instead of the WISC-IV). In my opinion, acting on this advice does no favors to children with autism and may even result in harm.

Based on the evidence presented in the study, the average score differences between children with and without autism is smaller on Raven’s Progressive Matrices (RPM) and larger on the WISC-IV. The rhetoric of the introduction leaves the reader with the impression that the RPM is a better test of intelligence than the WISC-IV. Once we accept this, it is easy to discount the results of the WISC-IV and focus primarily on the RPM.

There is a seductive undercurrent to the argument: If you advocate for children with autism, don’t you want to show that they are more intelligent rather than less intelligent? Yes, of course! Doesn’t it seem harmful to give a test that will show that children with autism are less intelligent? It certainly seems so!

Such rhetoric reveals a fundamental misunderstanding of what individual intelligence tests like the WISC-IV are designed to do. In the vast majority of settings, they are not for certifying how intelligent a person is (whatever that means!). Their primary purpose is to help psychologists understand what a person can and cannot do. They are designed to help explain what is easy and what is difficult for a person so that appropriate interventions can be selected.

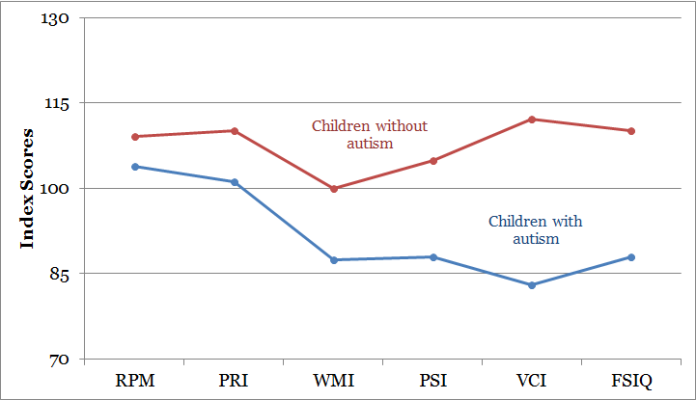

The WISC-IV provides a Full Scale IQ, which gives an overall summary of cognitive functions. However, it also gives more detailed information about various aspects of ability. Here is a graph I constructed from Figure 1 in the paper. In my graph, I converted percentiles to index scores and rearranged the order of the scores to facilitate interpretation.

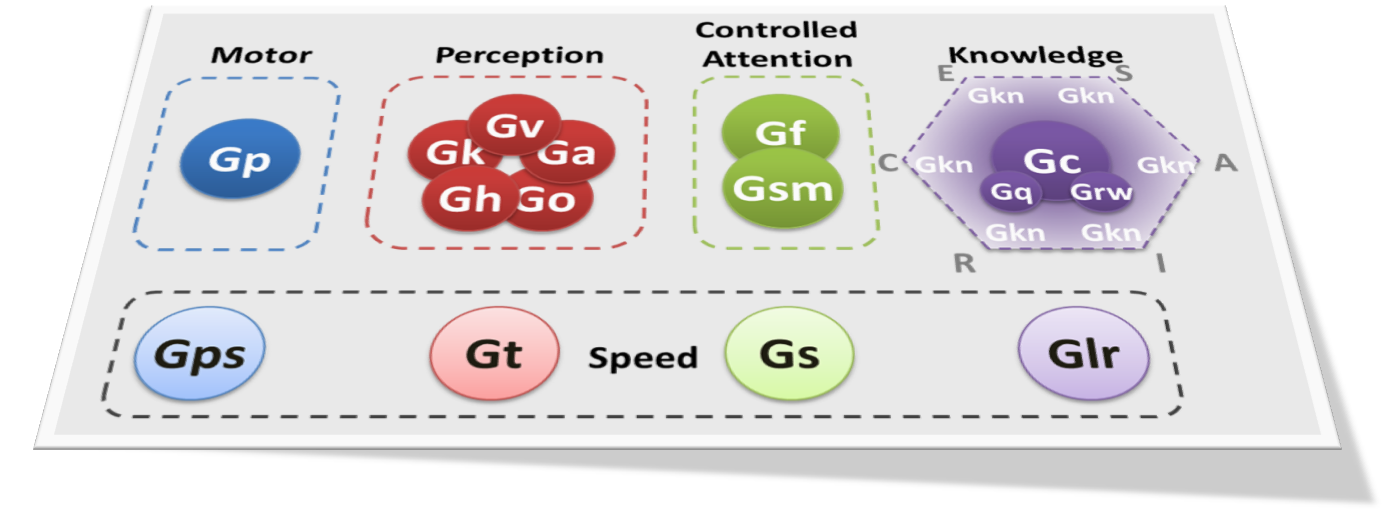

It is clear that the difference between the two groups of children is small for the RPM. It is also clear that the difference is also small for the WISC-IV Perceptual Reasoning Index (PRI). Why is this? The RPM and the PRI are both nonverbal measures of logical reasoning (AKA fluid intelligence). Both the WISC-IV and the RPM tell us that, on average, children with autism perform relatively well in this domain. The RPM is a great test, but it has no more to tell us. In contrast, the WISC-IV not only tells us what children with autism, on average, do relatively well, but also what they typically have difficulty with.

It is no surprise that the largest difference is in the Verbal Comprehension Index (VCI), a measure of verbal knowledge and language comprehension. Communication problems are a major component of the definition of autism. If children with autism had performed equally well on the VCI, we would wonder whether the VCI was really measuring what it was supposed to measure. Note that I am not saying that a low score on VCI is a requirement for the diagnosis of autism or that the VCI is the best measure of the kinds of language problems that are characteristic of autism. Rather, I am saying that children with autism, on average, have difficulties with language comprehension and that this difference is manifest to some degree in the WISC-IV scores.

The WISC-IV scores also suggest that, on average, children with autism not only have lower scores in verbal knowledge and comprehension, they are more likely to have other cognitive deficits, including in verbal working memory (as measured by the WMI) and information processing speed (as measured by the PSI).

Thus, as a clinical instrument, the WISC-IV performs its purpose reasonably well. Compared to the RPM, it gives a more complete picture of the kinds of cognitive strengths and weaknesses that are common in children with autism.

If the researchers wish to demonstrate that the WISC-IV truly underestimates the intelligence of children with autism, they would need to show that it underpredicts important life outcomes among this population. For example, suppose we compare children with and without autism who score similarly low on the WISC-IV. If the WISC-IV underestimated the intelligence of children with autism, they would be expected to do better in school than the low-scoring children without autism. Obviously, a sophisticated analysis of this matter would involve a more complex research design, but in principle this is the kind of result that would be needed to show that the WISC-IV is a poor measure of cognitive abilities for children with autism.