Charles Scherbaum and Harold Goldstein took an innovative approach to editing a special issue of Human Resource Management Review. They asked prominent I/O psychologists to collaborate with scholars from other disciplines to explore how advances in intelligence research might be incorporated into our understanding of the role of intelligence in the workplace.

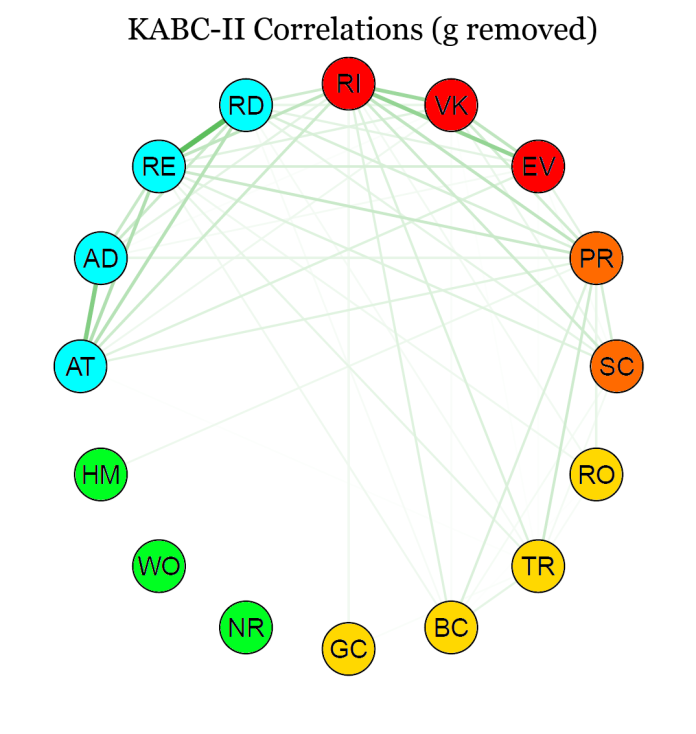

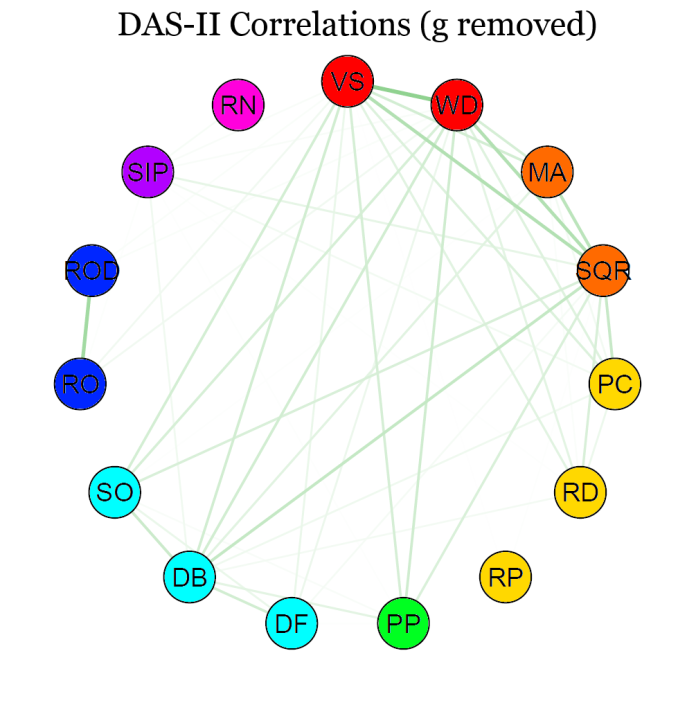

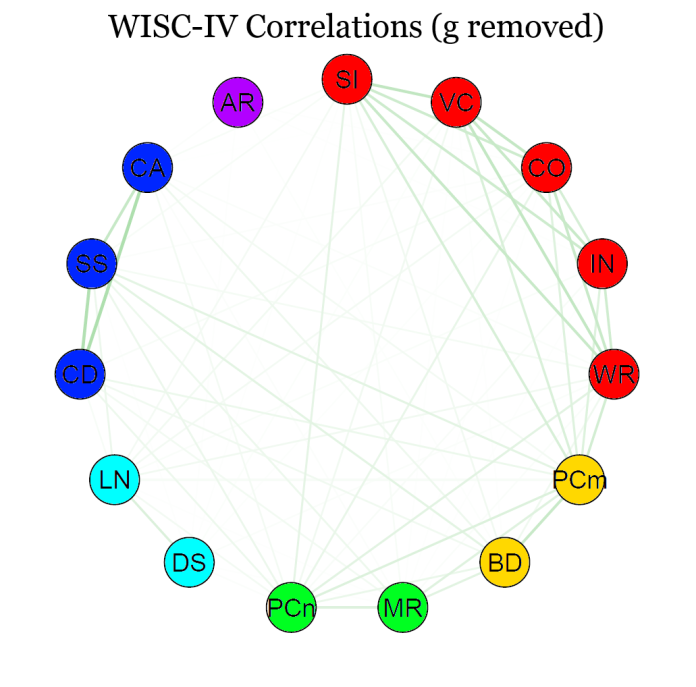

It was an honor to be invited to participate, and it was a pleasure to be paired to work with Daniel Newman of the University of Illinois at Urbana/Champaign. Together we wrote an I/O psychology-friendly introduction to current psychometric theories of cognitive abilities, emphasizing Kevin McGrew‘s CHC theory. Before that could be done, we had to articulate compelling reasons I/O psychologists should care about assessing multiple cognitive abilities. This was a harder sell than I had anticipated.

Formal cognitive testing is not a part of most hiring decisions, though I imagine that employers typically have at least a vague sense of how bright job applicants are. When the hiring process does include formal cognitive testing, typically only general ability tests are used. Robust relationships between various aspects of job performance and general ability test scores have been established.

In comparison, the idea that multiple abilities should be measured and used in personnel selection decisions has not fared well in the marketplace of ideas. To explain this, there is no need to appeal to some conspiracy of test developers. I’m sure that they would love to develop and sell large, expensive, and complex test batteries to businesses. There is also no need to suppose that I/O psychology is peculiarly infected with a particularly virulent strain of g zealotry and that proponents of multiple ability theories have been unfairly excluded.

To the contrary, specific ability assessment has been given quite a bit of attention in the I/O psychology literature, mostly from researchers sympathetic to the idea of going beyond the assessment of general ability. Dozens (if not hundreds) of high-quality studies were conducted to test whether using specific ability measures added useful information beyond general ability measures. In general, specific ability measures provide only modest amounts of additional information beyond what can be had from general ability scores (ΔR2 ≈ 0.02–0.06). In most cases, this incremental validity was not large enough to justify the added time, effort, and expense needed to measure multiple specific abilities. Thus it makes sense that relatively short measures of general ability have been preferred to longer, more complex measures of multiple abilities.

However, there are several reasons that the omission of specific ability tests in hiring decisions should be reexamined:

- Since the time that those high quality studies were conducted, multidimensional theories of intelligence have advanced, and we have a better sense of which specific abilities might be important for specific tasks (e.g., working memory capacity for air traffic controllers). The tests measuring these specific abilities have also improved considerably.

- With computerized administration, scoring, and interpretation, the cost of assessment and interpretation of multiple abilities is potentially far lower than it was in the past. Organizations that make use of the admittedly modest incremental validity of specific ability assessments would likely have a small but substantial advantage over organizations that do not. Over the long run, small advantages often accumulate into large advantages.

- Measurement of specific abilities opens up degrees of freedom in balancing the need to maintain the predictive validity of cognitive ability assessments and the need to reduce the adverse impact on applicants from disadvantaged minority groups that can occur when using such assessments. Thus, organizations can benefit from using cognitive ability assessments in hiring decisions without sacrificing the benefits of diversity.

The publishers of Human Resource Management Review have made our paper available to download for free until January 25th, 2015.