Some people did not like my post suggesting that attention tests are really important for understanding a person but that they are not awesome in every way that a test can be awesome.

I’ve found their arguments to be persuasive and now have an updated position:

It Isn’t “ADHD” Unless You Fail My Tests

ADHD is a problem. Is it even real?

If it is real, who has it? For really real, I mean.

What doesn’t work:

- We cannot trust self-reports, for sure. Kids don’t know anything and adults—well, Ritalin junkies will say or do anything.

- Parent and teacher rating scales? Don’t get me started.

- Interviews? Unstandardized rating scales in conversation form. A lotta yada yada for a lotta nada nada.

- Comprehensive reviews of school records? Are there any studies with real data proving that this works?

- Direct observation? That’s for grad students and research studies! Who has the time? I’ll “observe” during testing.

- A comprehensive consideration of all the available evidence, including attention tests? Well, this is the obvious answer people give. It does seem like a reasonable answer but in reality it is not. Too expensive, too much work, and too much “peace, love, & rainbows” if you know what I mean.

What does work:

We need objectivity and we need it quick! Like brain scans or something—but less expensive. Like tests, especially computerized ones with T-scores rounded to 2 decimals of precision.

The good news is that the tests we already have are great. And there are so many of them! If a person performs well on one test, there is always another one you can give. There is a low score in that profile somewhere…

When you find a low score, give the test again for the sake of reliability. Or an alternate form. If the score isn’t low the second time around, keep looking. Usually you won’t have to look long—it’s a rare person who does well on everything. If the person is really smart, count an average score as a deficit.

Whatever the low score is, as long as seems like it measures attention, it is probably the explanation you are looking for. Consult the research literature….Oh good! There was a study once that showed that this test was correlated with…problems (p < 0.05).

Don’t listen to people who claim that our knowledge about ADHD is limited. Ever gone to a library? Those things are freaking huge! And there are lots of them. In universities, even. In one of those books or in one of those journals, somebody with a Ph.D. said something about something (more p-values) that totally agrees with you. Find it. Cite it. There might be more than one study. The Internet can help. Don’t tell me that knowledge is limited until you’ve read everything.

Talking with Evaluees

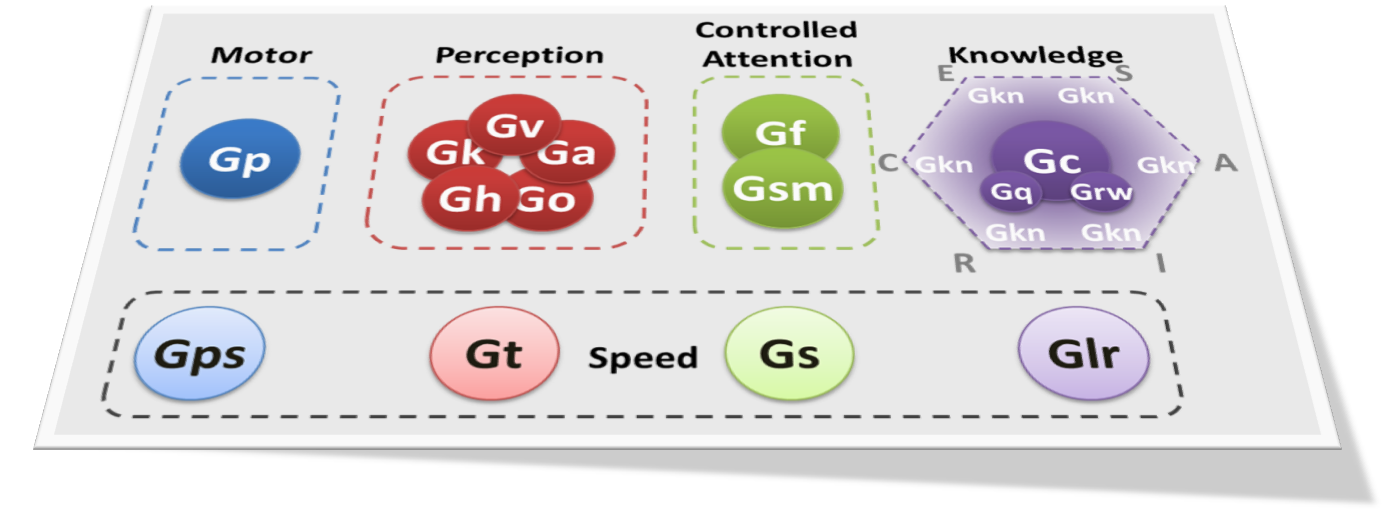

Now that the explanation has been found, explain to the person that his or her attention problems are really a manifestation of something deeper: executive function deficits. Explain that executive functions are like attention but fancier. Because working memory. Point to a picture of the frontal lobes. There are lots of studies about the brain (p < 0.05).

The goal here is to be right. And you can always be right. You sacrificed your 20s for that degree…you earned the privilege never to be questioned.

Speaking of being questioned, what’s with these people who claim to have attention problems and then reject my non-diagnosis of ADHD because of good test performance? Liars all! Or whiners. Or both. Lying whiners are the worst! I tell them:

“Look, you are completely normal. I’ve seen people with problems way worse than yours. They failed my tests. They have ADHD. You don’t. If you did, you’d’ve have failed my tests. I know, I know—your life is a mess, your work history is spotty, and that you have a long history of failed relationships. There’s no need to call this ADHD. Maybe you should try harder to pay attention to things and do them right—like you did on my tests. Ever think of that? It’s a shame because you’re a bright guy. I’m not just saying that to be nice—you did really well on my tests. You should’ve finished your college degree—nevermind…water under the bridge! I see you’ve been in a number of car accidents. Be safe! Also, return your library books on time—you’re losing a lot of money that way. Get more sleep. Don’t procrastinate any more either—that’s half your problem right there. The amount of time that you play video games is not healthy. All things in moderation as they say! I don’t mean to be rude but I’d like to give you some constructive criticism: When I am trying to say something, you often interrupt with things you are thinking about. Sometimes it isn’t even relevant to what I was saying. I do want to hear you but I did find it a little annoying. I bet other people don’t appreciate it either. A little courtesy goes a long way…I’m just being honest. One more thing, when your wife was here, she said that you mean well but often fail to follow though with things and that she can’t trust you with anything time-sensitive. She seems real nice but if you keep letting her down like that…you are going to lose her. I thought you should know. Keep your promises and things should get a lot better. Okay, now…on your way. Good luck!”